“The British constitution has always been puzzling and always will be.”

- Queen Elizabeth II

Introduction

It is common knowledge that the United Kingdom has never codified its constitution. In taking this path, our constitution is bestowed with the unique capacity to change with the times, paying due respect to the centuries of tradition that has afforded our ancient rights and freedoms. Our constitution is inherently political in nature. It has basis in law, but is subject to change through the democratic process of the King-in-Parliament; the sovereign lawmaking body in this country.

This page will seek to identify some of the cornerstones, explain them in detail, and serve as a guide with which to interpret the role and extent of constitutional law in the United Kingdom.

We understand the following to be the core elements of the constitution:

-

Government by the people

-

Government by party

-

The Houses of Parliament

-

The Monarchy

Government by the people

“The people of the United Kingdom have in their hands, as clay, a constitution which they have, and will continue to, mould in the image of their ideal society. Through electing Parliaments, they make their sovereign will known.”

Government by the people is a maxim that pervades many Western democracies. It is no less true of the British constitutional system that the people have the power to persuade politicians of the day to recognise the need to bow to public opinion. Through capturing the imagination of the sovereign electorate, the constitution of the United Kingdom has become an organ of democracy. It is no longer the case that a cosy aristocracy directs the conversation of the nation or public opinion, but those conversations which take place in the public house, the shop, and the street.

People who have the vote must be persuaded. Where they are ignorant of political problems such that they can be “stampeded by slogans or specious promises or allegations of unknown terrors”, or if they “do not see that acquiescence in a corrupt government is to take part in a conspiracy to establish tyranny”, a wide but uninformed franchise is the path to demagoguery and dictatorship.

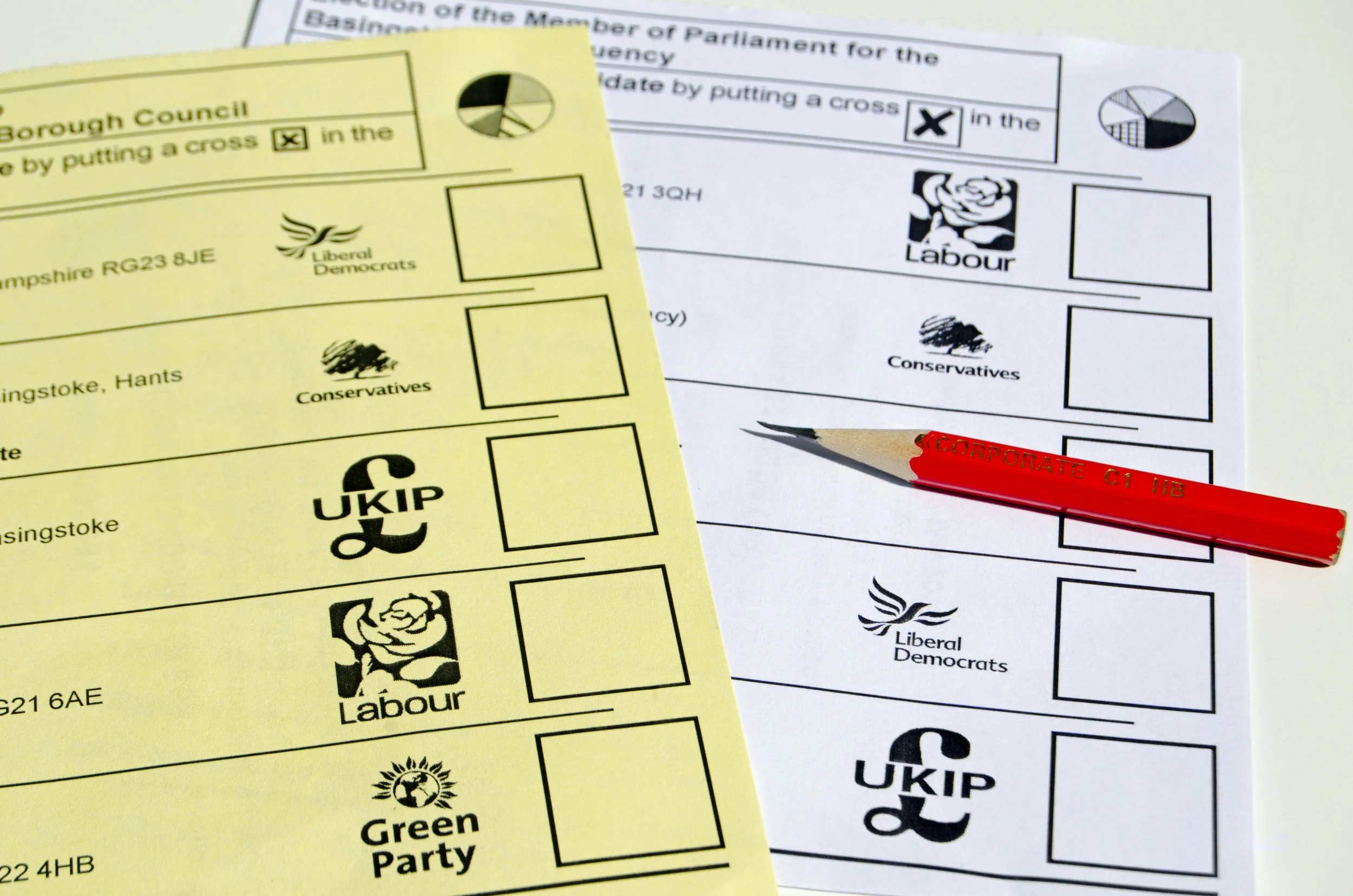

It is not merely a wide, well-informed franchise that governs the success of a democracy. Rather, it is the following cardinal factors: free and fair elections (upon which the character of the government depends solely), exercised secretly; and a choice between rival candidates advocating rival policies. This has differentiated British constitutional democracy from the ‘people’s democracy’ of communist states, and from the autocratic systems of other authoritarian jurisdictions.

Each Parliament must begin, and end. It is a constitutional necessity. There must be a general election at least once every five years; and the law has provided this from at least 1716 (in the form of The Septennial Act 1716 (1 Geo 1 St 2 c 38); amended down the centuries. This is a rule of law. It can be changed, as is evidenced, but not without the assent of both Houses of Parliament (with the Commons notably being unable to overrule the Lords on matters pertaining to the maximum duration of Parliament).

Thus, we come to the root of the matter. The people of the United Kingdom have in their hands, as clay, a constitution which they have, and will continue to, mould in the image of their ideal society. By electing Parliaments, they make their sovereign will known. A party that seeks election must present a mandate for the people to decide on at the ballot box. A Party is an agglomeration of Members of Parliament (explained below) who broadly agree on affairs of state. But through choosing a representative which is best for them, the constitution provides for the greatest outlet of democracy at the most local level – one constituency, one vote to each person, and one representative.

Government by party

“They [parties] carry forward that which is required to secure an election victory, for the proportion of uncommitted sovereign electors is enough to determine the fate of any Party. They galvanise the people, helping to put long-standing principles into plain English, and enact policies that are in the collective welfare.”

It is not difficult to defend the notion that the British Parliamentary system was the progenitor of the political party. It is yet another aspect, provided for through the custom of our constitution, that has developed out of a longstanding rejection of authoritarian “Councils of State”. It represents the truly democratic suspicion that an individual may not always be right, and so a conglomeration of individuals who present articulate consensus is a better check-and-balance in times of controversy.

At the heart of government by Party is tolerance. A principle that has governed political machinations in Britain for centuries, carried out in its laws, it remains an attitude of mind. Because the majority of any democratic nation is never permanent, tolerance of different views has a strong root in our constitutional arrangement. Not only do opinions fluctuate, but they sometimes fluctuate violently, and a significant feature of British politics is the “swing of the pendulum”.

What drives our politicians to conglomerate into Parties, instead of standing on their own merits? It hearkens back to what was said above. Collaboration, based on a set of principles, and the resolution of political differences being most conducive to the majority reaping the rewards of co-operation.

No party in the United Kingdom is founded upon an essentially unchangeable factor. You will not find a Labour Party comprised entirely of socialists, nor a Conservative Party of capitalists. Neither Party will draw its members from entirely one caste, class or creed. A wide range of members is the mainstay of consensus, and for proving the worthiness of a mandate to the electorate. The rise of the Labour Party in the first half of the 20th Century and the call for socialism did not fundamentally change the makeup of how we decide who to elect, the ways in which they put their mandate to the electorate, or the framework which they are governed by. They are beholden to a set of principles, agreed upon, handed down through collaboration and exchange, which the people have shaped to their collective belief in the welfare of society.

The Parties, as it is well-known, gather in Parliament, a sacred chamber of democracy and resolution of conflict. The policy decided upon when they come together is dependent upon the currents of public opinion. By contrast, in a dictatorship, freedom of speech and thought is muzzled, and it is difficult to ascertain what the prevailing opinion is. Britain, by its constitutional settlement, is confident in being quite the opposite. It leads, in most instances at least, to common sense prevailing, for politicians conglomerated into parties must, on the whole, federate themselves to the interests of their Party, inevitably bringing out the reasonable in them.

The purpose of the Party, therefore, is to support the Government in carrying out the policy of the party; or if in Opposition, to criticise the Government insofar as it fails to carry out its own mandate promised to the electorate. The Opposition must always be mindful that it will likely be in government within the decade, and so should responsibly keep its own fingers on the pulse of the nation. It should not oppose for the sake of opposition, or merely obstruct the business of government, but table important considerations which may point to flaws in the mandate of the ruling party.

It follows that Government decisions, and Opposition criticisms, are abed in a long history of politicians that have come before the Parties of today. Each steps into the shoes of Opposition and Government, but those shoes rightfully belong to a gradually eked out constitution of custom, convention and inherited wisdom.

Then what is ‘Party policy’, and its role in the constitution? It, too, reaches down the centuries and culminates ever in the present. Guiding hands from ages long since past shape that which is attractive to the modern Britons, and it reaches down through custom and convention because we are in effect the same people enjoying the same settlement as those two hundred years ago.

The role of Parties in the British constitution can aptly be summed up in their role as vehicles. In their capacity as vehicles, they carry forward that which is required to secure an election victory, for the proportion of uncommitted sovereign electors is enough to determine the fate of any Party. They galvanise the people, helping to put long-standing principles into plain English, and enact policies that are in the collective welfare. The constitution provides for them because they are conducive to collaboration, consensus and custom, three ‘C’s’ that the constitution repeatedly returns to.

The Houses of Parliament

“The House of Commons is, under the constitution, the effective legislative authority in Great Britain, enjoying the right to impose taxes and vote money to, or withhold it form, various public departments and services.”

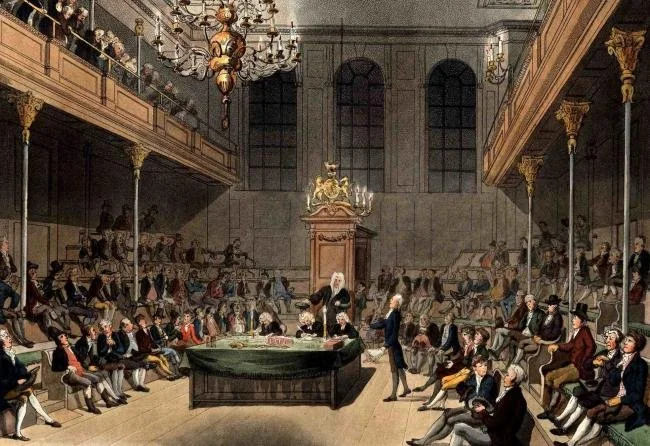

The House of Commons 1783-94 by Karl Anton Hickel

The House of Commons is the popularly elected legislative body of the bicameral Houses of Parliament of the United Kingdom. While technically, and traditionally, it is known as the ‘lower’ house, it is predominant of the House of Lords.

The Origins of the House of Commons date from the second half of the 13th Century. Landholders and other owners of property in the counties and towns of England gradually began to send representatives to Parliament, to present their grievances and petitions to the king, and to accept commitments to the payment of taxes. This is still the main function of the Commons today, unchanged for hundreds of years. Members of Parliament hear the grievances of their constituents and present them to His Majesty’s government, who all still advise the Sovereign on all affairs of state.

The House of Commons is, under the constitution, the effective legislative authority in Great Britain, enjoying the right to impose taxes and vote money to, or withhold it from, various public departments and services. Nevertheless, there are important functions reserved by the Lords, and the Sovereign, that act as constitutional checks and balances on the power of the Commons.

The primary function of the Commons is to initiate the passage of legislation. It proceeds from the Party who holds the majority in the Commons, who forms the government and the Cabinet (all appointments must be recommended to the Sovereign, who then approves them). The Cabinet is comprised of senior ministers chosen by, and belonging to the party of, the Prime Minister, nearly all of whom serve in the Commons, but may come from the Lords if a majority is held there.

The constitutional theory is that the Government controls the House. The Government, however, is responsible to the House. In this sense, the Government directs the business of the House, but the House holds the Government to account. Because there is a vested interest in a member of the Government’s majority staying in power, there will almost always be obedience by the Party in government to support the Government.

Much of this has made the constitutional role of the Commons sound very much like a dictatorship. But it is not so. Dictators who at short intervals have to beg the people for votes freely cast are the servants of the public, and not its masters. There is a most important apparatus that prevents the Commons from abusing its constitutional authority, and that is His Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition.

Facing the Government, always, is the Opposition. If Parliament’s main function is to criticise, the Opposition is its most important are, for they are critics by profession. Unlike most other legislatures, the chamber of the Commons is arranged not as a semi-circle, but as two large blocks separated by a gangway. It is adversarial. The members of the Government sit on the front bench to the right of the Speaker of the House, and the leaders of the Opposition on the front bench to their left.

Thus, what the constitution demands, is not conformity, but the opposite. The Government governs through its majority, but it must do so under constant barrages of criticism from the Opposition, which in effect comprises every Member who is not in the Party of Government. Outside of the House, opinion is assumed to be divided. Ministers must answer argument by argument, defending their policies, and meeting half-truth with a whole truth.

Debate is central to the Constitution. It has the capacity to embarrass the Government, prevent it from running away without telling the truth. An effective Opposition is a constitutional necessity; the whole cathedral suffers if the Opposition does not do its duty under the constitution. Note, however, its business is not to obstruct government for the sake of obstruction. Its purpose is to criticise, not to hinder.

“The advantages of a second chamber, therefore, are clear. The ability to focus on the bill, and the bill alone, mostly independent of Party interests, is a valuable tool. Not only can the Peers keep their ear close to the mind of the nation, they also deal directly with it, refining bills from the Commons into something which genuinely represents the national interest, and not merely as the politicians understand it.”

House of Lords, 1961–1962, Portrait of Peers by Alfred Reginald Thomson

The House of Lords is the upper chamber of the bicameral legislature of the United Kingdom. It originated in the 11th Century, making it the older of the two chambers. It emerged as a distinctly separate place in the 13th and 14th Centuries. It continues to be comprised of two centuries-old elements: The Lords Spiritual, which includes the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, and the Bishops of Durham, London, and Winchester, of England’s Established Church, the Church of England. It is also comprised of the Lords Temporal, which from November 1999, includes 92 hereditary peers (who have inherited their right to sit in the Lords) and all Life Peers and peeresses created under the Life Peerages Act of 1958.

The House of Lords’ modern powers are quite limited, by the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949. As mentioned above, all bills which are defined as money bills (concerning taxation or expenditure) become law one month after being sent for consideration to the Lords, with or without the consent of that House. Under the 1949 Act, all other public bills (except those which extend the maximum duration of Parliament) not receiving the approval of the Lords become law, provided that they are passed by two successive sessions of Parliament and that a period of one year has elapsed between the second reading of the bill in the first session, and its third reading in the second session (by tradition, bills appear before both Houses three times before they go to the Sovereign for royal assent).

On rare occasions, the 1949 Act has been invoked to pass controversial legislation that lacked the Lords’ support. The quite commonly invoked Salisbury Convention of 1945 prevents the Lords from rejecting a bill at second reading (which is the principal stage at which parliamentary bills are debated) if it fulfils any of the Government’s manifesto pledges.

In 1998 the Labour government of Tony Blair introduced legislation to deprive hereditary peers (by then numbering 750) of their 700-year-old right to sit and vote in the upper chamber. This was a prelude to wider reform that never took place. As such, the current makeup of the House of Lords is overwhelmingly of Life Peers – those who the Government of the day have sent to the Upper House through the ennoblement procedures in the Life Peerages Act 1958.

In their traditional constitutional role, therefore, the Lords are the greatest representation of an apolitical chamber, which can focus alone on the important aspects of legislation that comes before it. It is an essential counterweight against the politicised Members of the House of Commons, who are subject to outside pressures, and their own Party whips. Parties in Government may institute rash, immature plans of social reform, that if carried out, would be dangerous to the peace or economic stability of the country. The Lords still retain the capacity to slow that legislation down, point out its weaknesses, and send it back to the Commons for further debate. Put simply, they can halt measures of a radical nature until the ‘mind of the country’ has been made up.

A radical Government, therefore, is kept from changing the entire face of the constitution as we understand it. In particular, the hereditaries who remain, the Lords are the sacred guardians of the constitution, along with the Sovereign, for in tradition they were closer to the Sovereign than the representatives of landowners and burghers who were despatched to sit in the Commons.

It joins a number of checks and balances that the constitution provides for. The ultimate power of the electorate is the greatest check on the power of the Commons. Nevertheless, there exists this important body of individuals, many now of whom have held political station, who understand the system, and the process of legislation, to such an extent that they may refine bills into those which more accurately represent the “mind of the country”. Is a second chamber desirable at all? We can state in the first place that the answer to that is a resounding yes. The House debates general issues of policy, not party politics. These debates are short, straight to the point, and those who are taking part are typically peers with experience as a minister, governor-general, ambassador or otherwise. A peer really speaks for the sake of speaking, and in the Lords, there is no necessity to ‘keep the debate going; the business is put forward and then dealt with. These debates, while not essential, are useful, and will more often than not pick up on several matters that the Commons has neglected.

In the second place, the House retains its role as a legislative chamber. Bills may be introduced in the Lords. Bills that deal with subjects of a “partially non-controversial character”, if they are worked out beforehand, might have an easier passage through the Commons, where discussion has already been put into it. When the esteemed Law Lords (senior judges who also sat in their own right as peers in the House of Lords) sat in the House, they would regularly suggest useful amendments, particularly if the Bill concerns law reform. The Law Lords now no longer exist, separated from the legislative process and placed in their own court.

In the third place, the House of Lords continues to debate bills that are brought up from the House of Commons. It is still for the Lords to catch which the Commons has missed. Very regularly are amendments successfully introduced to bills, even if the nature of that bill is a ‘public bill’ (concerning some matter of public interest).

And in the fourth place, perhaps their most important role is to undertake a mass of work on Government legislation that takes place outside of Government time and Parliamentary debating hours. Suggestions for improvement will pour in so long as the bill is in Parliament, and indeed long after the bill has passed. The role of the peers, then, is to sit in the lengthy Committee Stage of the bill to ensure that these suggestions are given a voice. They are usually suggested by independent charities, government agencies, or sometimes lobbyists with interests in an upcoming change in the law. Very regularly, the peers will have technical experience in the field that the bill is concerned with. The Lords work outside of the limelight and ensure that the bill most accurately respects public sentiment, which they can do in their capacity as being responsible unto themselves.

The advantages of a second chamber, therefore, are clear. The ability to focus on the bill, and the bill alone, mostly independent of Party interests, is a valuable tool. Not only can the Peers keep their ear close to the mind of the nation, but they also deal directly with it, refining bills from the Commons into something which genuinely represents the national interest, and not merely as the politicians understand it.

The Monarchy

“‘King and Country’ sustained the British people throughout two World Wars. The same immense popularity for the monarchy as a unifying force continues today. Each action of the Sovereign serves to create a common sentiment because he is a servant to his nation”

St. Edward’s Crown

The Sovereign has a key role. And it is the role on which all other parts of the Constitution depend for their proper function. That is the appointment of the Prime Minister. Somewhere, in every constitution, there must be someone who takes the first step to form a Government when a gap is threatened. And for the United Kingdom, that role is occupied by His Majesty.

In every case, the Party victorious at the election will hold a miniature election amongst themselves, to propose a candidate and advise His Majesty that they should be the one who should become Prime Minister. And yet, it is essential to note, this advice does not bind the Sovereign. Moreover, the Sovereign has a choice in two cases: when the Party has a majority but no leader, or when no party has a majority. In the former case, the sovereign must appoint a Prime Minister who can command the willing support of the party majority.

There have been historical situations where the Sovereign refused to ask for the advice of the outgoing Prime Minister. For instance, Queen Victoria did not ask Gladstone’s advice in 1894 and had already decided to send for Lord Rosebery. Nor was it certain that Edward VII asked Lord Salisbury’s advice in 1902, or again in 1908 as to whether Campbell-Bannerman was consulted. Even if a new procedure for putting the most popular Party figure in front of the Sovereign is developed, the Sovereign’s prerogative in this matter remains unaffected.

The function is equally important where no party has obtained a majority, or the position has become complicated (perhaps closest to this situation was the debacle in the latter half of 2019, where Parliament was paralysed). The resignation of Stanley Baldwin’s government in 1924 saw George V called upon to decide whether to summon Asquith of the Liberal Party, or Ramsay MacDonald as leader of the Labour Party, to form a government, or try to form a coalition, sending for MacDonald in the end. There was an even more complicated situation in 1931, where the Labour Government, with no majority, had resigned, and the nation was suffering a financial crisis, with a general election being out of the question. The King commissioned MacDonald to form a coalition, being much criticised for doing so, but this act was not unconstitutional.

These examples, although infrequent (thanks to the harmony of the system as presided over by the Sovereign), show the importance of the monarchy as a stabilising force. The monarch is in a naturally advantageous position, being both ‘above’ politics, and being able to remain in close contact with the Government.

In many other cases the Sovereign exercises functions, many of them formal:

The Sovereign is present at each meeting of the Privy Council, historically a council of specially selected individuals to advise the Sovereign (his presence is a maintained tradition to give such meetings legitimacy), exercising a very similar role today than it has in the past. It is chiefly a symbolic Council that brings the Sovereign into very close involvement with the business of government, but if a Draft Order in Council is brought up, the Minister concerned will attend and the King can ask for an explanation.

The Sovereign appoints Ministers, ambassadors, judges, and officers in the military and airforce, as well as senior civil servants.

The Sovereign prorogues and sums Parliament (typically in a grand ceremony, known as the State Opening of Parliament).

In nearly every case, he will act on the advice of his Ministers, signing Acts of Parliament into law with Royal Assent. This puts him in a position to ask for explanations and to give advice.

Even if no formal action is required, the King reserves an exclusive right to ask for explanations and to give advice

The Sovereign, to this day, receives a copy of the minutes of his Cabinet, and also of the ‘daily print’ of any communications circulated by the Foreign Office. He follows the debates in Parliament through the provision of an Official Report, supplementing that which is received from newspapers, personal inspections and interviews, as well as a staff to keep him informed of the developments of political life.

How may the Sovereign come to influence these events? It depends entirely on the Sovereign’s personal qualities. Qualities such as industry, and common sense, can be extremely valuable if used at the centre of affairs. It is the introduction of a refreshing, well-informed perspective, that might make all the difference in a politician looking more informed than they actually are. It is not unreasonable to think that advice and consultation from a Sovereign has saved many a politician’s skin. Much like a Minister, a Sovereign has a part to play in public, but unlike a Minister, the Sovereign is not beholden to glibly cling to matters of politics by virtue of their station.

Some historical examples include King George V and Stanley Baldwin, and Queen Victoria and Gladstone, who famously complained about the latter as ‘address[ing] me as if I were a public meeting’. The Sovereign therefore can do a world of good by simply injecting a little common sense.

What, then, can the Sovereign offer us? In his present constitutional role, a great deal. In the event that our ‘Trinity’ of Government, Party, and People run into a complete deadlock, the Sovereign may step in to exercise these important powers, laying dormant until they are needed to keep the business of government moving (which is in effect what the constitution is geared towards).

Outside of the exceptional constitutional functions, the Monarchy regularly exercises what Bagehot terms ‘dignified’ functions. As government is not simply the matter of giving orders and enforcing obedience, it is required that the willing collaboration of all sections of the people is obtained. Democracy is government by the people as well as for them. Individuals must, therefore, feel a personal responsibility for the exercise of collective action.

Monarchy, therefore, is an essential Fifth Column, a useful and important focus for patriotism. “King and Country” sustained the British people throughout two World Wars. The same immense popularity of the monarchy as a unifying force continues today. Each action of the Sovereign serves to create a common sentiment because he is a servant to his nation